Introduction to Category Theory: Functors

In our previous article, we introduced Category theory, a branch of mathematics that offers a way to study and understand structures and relationships between different mathematical objects in an abstract way. We also defined the concept of a category as a collection of objects and morphisms with an operation of composition, and explained how it can be used to model programming languages.

In this blog post, we will explore the concept of Functors in category theory. We’ll start by understanding why functors play such an important role in the composition of morphisms (or functions in software engineering), before introducing the definition of Functors and their basic properties and diving into some examples of how they can be used to map between categories and transform objects and morphisms.

Why should I care about Functors 🤔?

In the previous article we asked the following question:

We can compose two generic functions,

f: (a: A) => Bandg: (c: C) => D, as long asCis equal toB. However, what ifBis not equal toC? How can we compose two functions in such a scenario?

Understanding the importance of solving this problem is crucial since it is the major obstacle to composing two functions. Therefore, solving this abstract problem implies discovering a practical method of composing programs universally.

The general problem described above, cannot be solved with our current set of rules; we need to define some boundaries for both B and C.

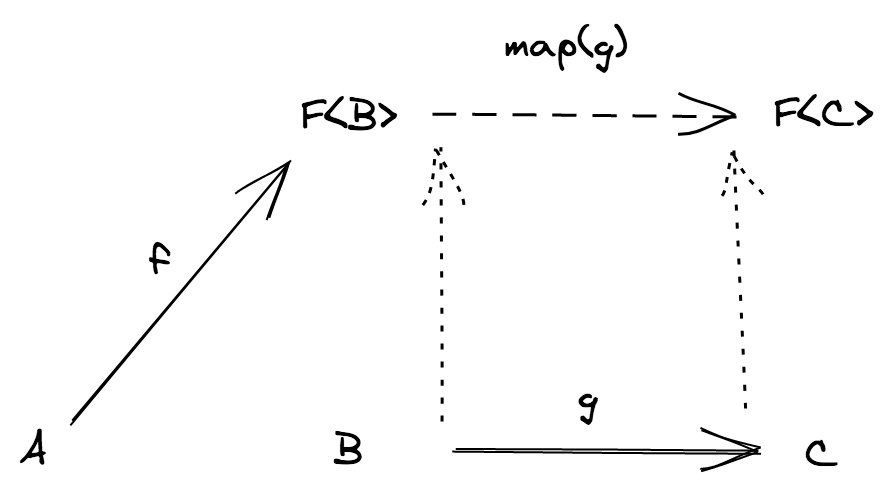

Let’s consider the following boundary: B = F<C> for some type constructor F, we have the following situation:

f: (a: A) => F<B>is an effectful programg: (b: B) => Cis a pure program

Note 💡: We call “Effectful program” a program with the following signature

(a: A) => F<B>. This program takes an input type ofAand returns a result of typeBtogether with an effectFwhereFis some sort type constructor. More generally, when a type constructorFadmits a map function, we say it admits a functor instance.

Example:

import { Option } from "fp-ts/Option"; const fromNullable = <A>(a?: A | null): Option<A> => a == null ? Option.none : Option.some(a);

To combine f and g, we require a method to transform a function (b: B) => C into a function (fb: F<B>) => F<C>. This allows us to utilize standard function composition and ensures that the codomain of f is equivalent to the domain of the resulting function.

Mathematical Definition of a Functor

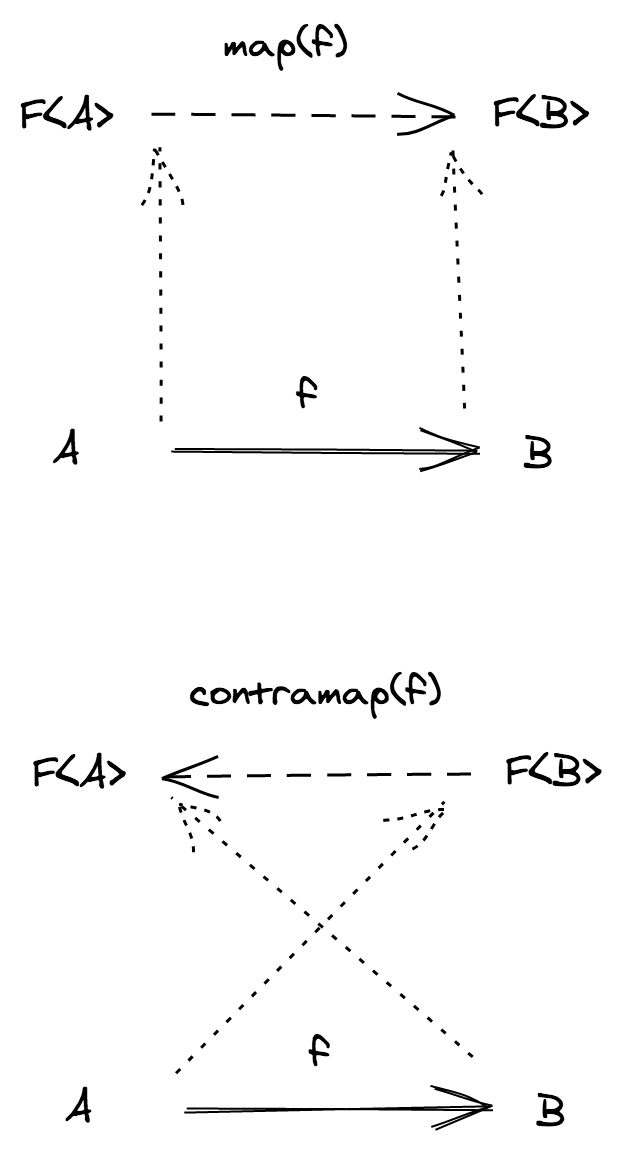

In category theory, a functor is a mathematical concept that describes the relationship between two categories. Specifically, a functor is a mapping or transformation between two categories that preserves the structure of the categories. This means that a functor maps objects in one category to objects in another category, and morphisms in one category to morphisms in the other category, while preserving the composition of morphisms and the identity morphisms. In essence, a functor is a mathematical tool that allows us to study the properties and relationships between categories.

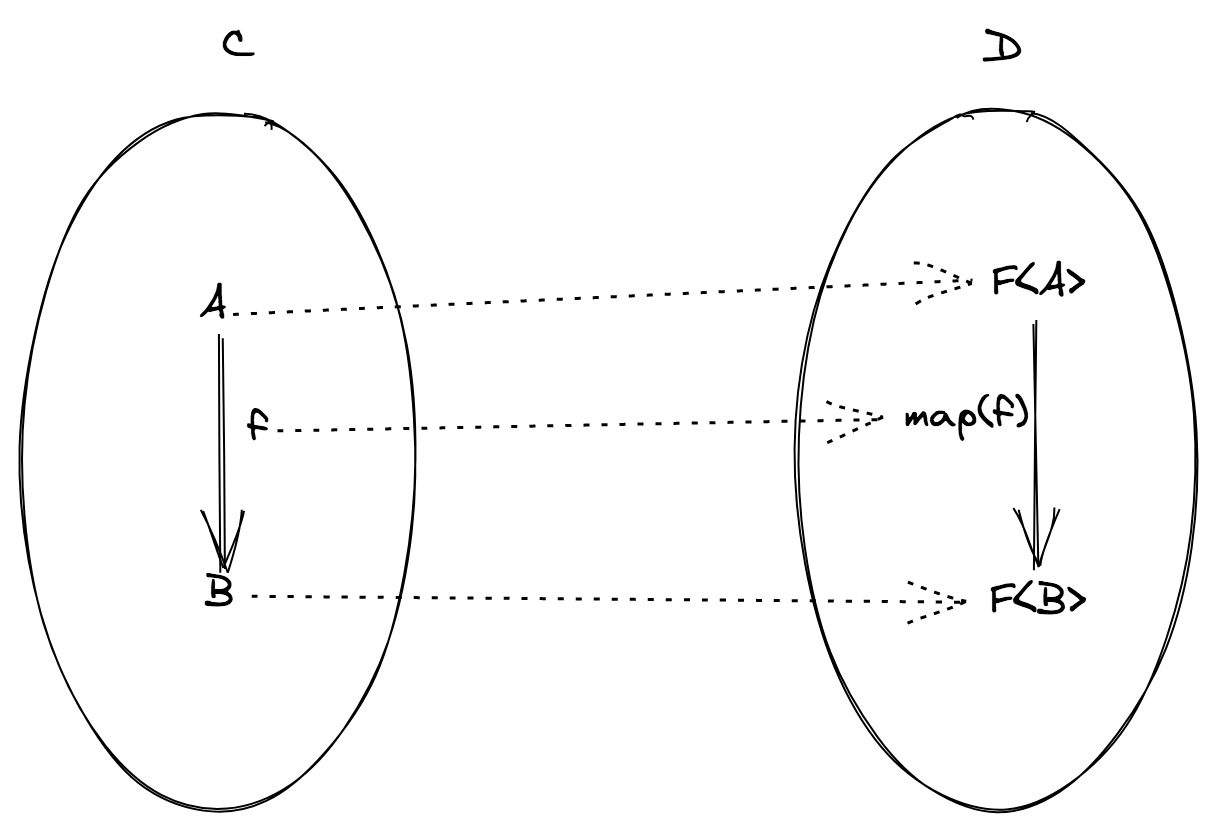

More formally, given two categories C and D, a functor F from C to D consists of:

- A mapping of objects: for every object

AinC, there is an objectF(A)inD. - A mapping of morphisms: for every morphism

f: A -> BinC, there is a morphismF(f): F(A) -> F(B)inD. - An identity-preserving property: for every object

AinC,F(idA) = id{F(A)}, whereidAis the identity morphism onAandid{F(A)}is the identity morphism onF(A). - A composition-preserving property: for every pair of composable morphisms

fandginC,F(g ∘ f) = F(g) ∘ F(f), whereg ∘ fdenotes the composition offandginCandF(g) ∘ F(f)denotes the composition ofF(f)andF(g)inD.

Note 💡: In the example above, C and D are two different categories; thus, they could be two different programming languages. While this is a fascinating idea, in this blog, we are more interested in a map or transformation between C and D that are the same. In that case, we are talking about

endofunctors(endo+functors, where endo comes from the Greek language, which means “internal”).

A great way to understand functors and the value that they bring to the table, is by taking a look into the following example:

import * as Either from "fp-ts/Either";

import { pipe } from "fp-ts/function";

type Json = ReturnType<(typeof JSON)["parse"]>;

// This function encapsulates some business logic

declare function parsedJsonToString(input: Json): string;

const parseJSON = (str: string): Either.Either<Error, Json> =>

Either.tryCatch(() => JSON.parse(str), Either.toError);

export const program = (str: string): Either.Either<Error, string> =>

pipe(str, parseJSON, Either.map(parsedJsonToString));I want you to pay extra attention to the Either.map function we used to get the value returned from the parseJSON function and convert it to a string. This is the functor that lets us take the happy path (the case in which parseJSON does not throw an error) and continue the pipeline by giving the value returned from parsedJSON to parsedJsonToString.

Contravariant Functors

Essentially, a contravariant functor has a definition that is similar to that of a covariant functor, except for the naming of its fundamental operation. In contrast to “map” used by covariant functors, contravariant functors use “contramap” for their operation signature.

Contravariant functors are a type of functor in category theory that invert the direction of arrows between categories. Specifically, if we have two categories A and B, a contravariant functor F: A -> B is a mapping that takes objects from A to objects in B, and morphisms from A to morphisms in B, but in the opposite direction. This means that if we have two objects a and b in A and a morphism f: a -> b, the contravariant functor F will take f to a morphism F(f): F(b) -> F(a) in B.

In other words if I have a functor F<A> and I apply a function of type B => A, I’ll get a F<B>!

Here’s an example:

import * as Ord from "fp-ts/Ord";

import { pipe } from "fp-ts/function";

interface Person {

name: string;

age: number;

}

// B => A or Person => Name(string)

const getName = (p: Person): string => p.name;

// Functor F<A> where A = string

const nameOrder: Ord.Ord<string> = Ord.ordString;

// Functor F<B> where B = Person

const personOrder: Ord.Ord<Person> = pipe(nameOrd, Ord.contramap(getName));

const people: Person[] = [

{ name: "Alice", age: 30 },

{ name: "Bob", age: 25 },

{ name: "Charlie", age: 40 },

];

console.log(people.sort(personOrder.compare)); // Sort by nameIn this example, we first define the getName function that takes a person and returns his name (string).

We than have the nameOrder which is of type of Ord<string> (F<A> where A = Name(string)). If we apply the contramap function of the Ord class to the nameOrd we get the personOrder which is of type of Ord<Person> (F<B> where B = Person). Voila! We just reversed the direction!

Do functors solve the general problem of composition 🤔?

The answer is unfortunately No. When we use functors, we can combine an effectful program f with a pure program g, but g must only take one argument. However, if g takes two or more arguments, we encounter a problem. We don’t know how to compose them. To handle this situation, we require a more advanced abstraction in functional programming known as applicative functors, which we will explore in the next chapter.

Conclusion

In this article we explained why functors are important in the composition of morphisms or functions in software engineering and how they can be used to map between categories and transform objects and morphisms. We also provided a mathematical definition of a functor and its properties and given examples to illustrate how they work.

In the upcoming article, we will delve deeper into the world of functional programming by exploring applicative functors. You will learn how these powerful abstractions can address the issue of composing an effectful program with a pure program that takes more than one argument.

So, don’t miss out and stay tuned for our next installment!